South Mediterranean AI Capacity Overview

| Country | AI Tier | Classification | Gov AI Readiness | ODIN 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🇲🇦 Morocco | T2 | AI Ready | 41.78 | 77/100 |

| 🇪🇬 Egypt | T2 | AI Ready | 55.63 | 53/100 |

| 🇯🇴 Jordan | T2 | AI Ready | 61.57 | 72/100 |

| 🇹🇳 Tunisia | T1 | AI Experimenter | 43.68 | 60/100 |

| 🇱🇧 Lebanon | T1 | AI Experimenter | 46.67 | 33/100 |

| 🇩🇿 Algeria | T1 | AI Experimenter | 39.06 | 28/100 |

| 🇵🇸 Palestine | T0 | AI Nascent | 37.53 | 75/100 |

| 🇱🇾 Libya | T0 | AI Nascent | 33.25 | 28/100 |

| 🇸🇾 Syria | T0 | AI Nascent | 16.95 | 28/100 |

Tier Definitions:

- T0 (AI Nascent): Very limited policy, infrastructure, or skills; AI largely absent from public-sector practice

- T1 (AI Experimenter): Early pilots and small projects; limited institutionalisation and scaling

- T2 (AI Ready): Basic enablers (data, infrastructure, skills, governance) in place for priority sectors

- T3 (AI Enabled): Systematic integration of AI across public services (none in region)

- T4 (AI Developer): Deployment at scale plus frontier model development (none in region)

Background

Adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly central to modern governance, but readiness to deploy and govern AI safely and equitably varies widely. In the South Mediterranean Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia and Palestine, structural vulnerabilities coexist with rapid digitalisation.

Objectives

- To compare AI capacity across South Mediterranean countries;

- To examine how AI strategies, open-data environments, and AI system capabilities interact;

- To propose a policy framework to move countries from “AI nascent” and “experimenter” tiers toward “AI enabled” tiers.

Methods

The study uses a mixed-methods approach, combining primary sources (official policies, strategies, and legal texts) with secondary data from the Government AI Readiness Index [1], the Open Data Inventory (ODIN) [5–6], OECD AI Capability Indicators [4], UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of AI and its Readiness Assessment Methodology (RAM) [2–3], and regional analyses by ESCWA and the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) [7–8,11]. Countries are assessed using the AI maturity tier framework of the UN Secretary-General (Tier 0–4), mapped onto five domains: (1) compute & infrastructure, (2) data & governance, (3) skills & institutions, (4) models & adoption, and (5) strategy & cooperation.

Results

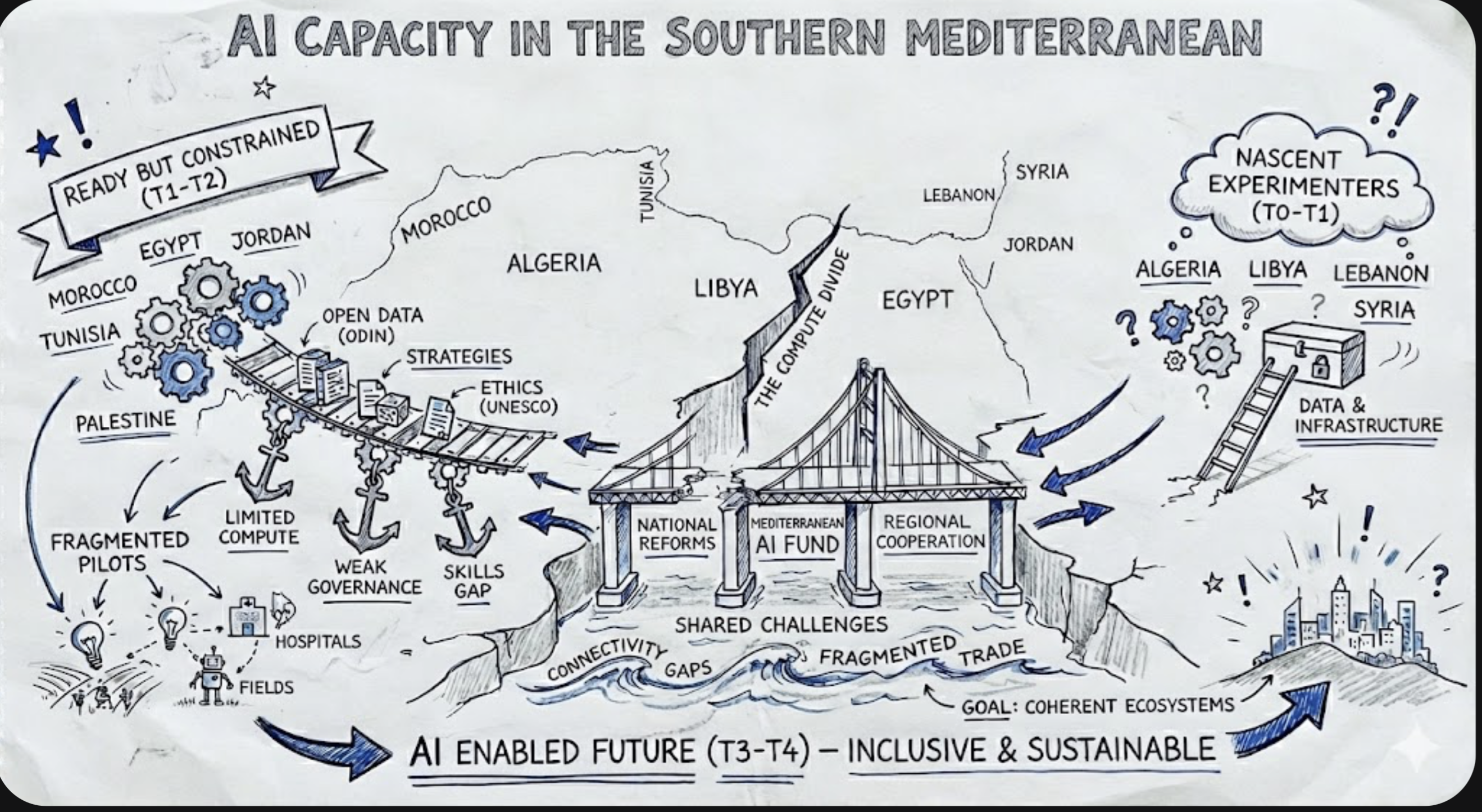

All assessed countries remain within Tier 0–2. Algeria, Lebanon, Libya, Syria and, to a lesser extent, Tunisia are largely “AI nascent” or “AI experimenters,” constrained by limited compute, weak data governance and modest AI-skilled workforces. Egypt, Jordan and Morocco emerge as “AI ready,” supported by national AI/digital strategies and higher AI readiness scores. Palestine combines a strong open-data system (ODIN ≈ 71–75) with emerging AI governance structures but limited compute and institutional capacity. Sector pilots in agriculture, health, education and mobility are visible but rarely scaled beyond experimentation. ODIN 2024 scores show Morocco (77), Palestine (75), Jordan (72) and Tunisia (60) outperforming Egypt (53) and significantly outscoring Algeria, Libya, Lebanon and Syria (≈28–33). OECD AI Capability Indicators underline that most countries depend on adapting high-capability global models to Arabic and local needs rather than developing frontier models locally [4]. UfM regional integration analysis confirms that uneven connectivity, fragmented digital-trade frameworks and weak cross-border data governance constrain AI scalability [7,11].

Conclusions

The region faces a two-speed AI trajectory: a small group of “ready but constrained” countries and a larger group of “nascent experimenters.” Without coordinated interventions, AI could exacerbate existing divides. However, improving open-data environments, emerging AI strategies, and growing attention to ethical AI norms provide a foundation for progress.

Policy Implications

Nationally, governments should adopt costed AI strategies, invest in data ecosystems and compute, institutionalise ethical AI, and expand AI-relevant skills. Regionally, Arab League, ESCWA and UfM platforms can support common AI norms, shared compute and data infrastructures, and cross-border research programmes focused on Arabic, local dialects (Darija, Egyptian Arabic, Levantine), Tamazight, Kabyle, and other low-resource languages of the Mediterranean.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence; AI readiness; South Mediterranean; AI governance; regional integration.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping public administration, service delivery and decision-making worldwide. Governments increasingly deploy AI for tasks ranging from eligibility screening and tax compliance to climate risk assessment and digital health, raising both opportunities and concerns about fairness, accountability and human rights.

Global initiatives such as the Government AI Readiness Index assess over 190 countries along government, technology sector, and data and infrastructure dimensions [1]. UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of AI and its Readiness Assessment Methodology (RAM) provide a normative and diagnostic backbone for ethical AI [2–3]. The OECD has recently introduced AI Capability Indicators to describe, at a system level, what AI models can do relative to human capabilities in areas like language, perception, problem-solving and creativity [4]. In parallel, the Open Data Inventory (ODIN) offers a systematic measure of the coverage and openness of official statistics, a critical foundation for data-driven AI [5–6]. Regional integration analyses by the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) and others link digital trade, connectivity and research collaboration to wider economic and political integration [7,11].

This paper focuses on the South Mediterranean: Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia and Palestine. It asks:

- How do these countries compare in terms of public-sector AI capacity?

- How do AI strategies, open-data environments and AI system capabilities interact?

- What national and regional policy frameworks are needed to progress from AI-nascent and experimenter tiers toward AI-enabled tiers?

2. Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

2.1 AI readiness and national strategies

AI readiness indices highlight government capacity, digital infrastructure and data ecosystems as preconditions for responsible AI adoption [1]. Regional analyses of AI strategies in Arab countries note that, despite a proliferation of strategy documents, many remain underfunded, with fragmented institutional arrangements and limited implementation [9–10]. This is particularly visible in countries facing fiscal and political constraints.

Palestine-specific work by Demaidi illustrates how national AI strategies can be adapted to developing-country contexts, emphasising law, education and entrepreneurship as key levers [9].

2.2 Ethical AI and UNESCO’s RAM

UNESCO’s 2021 Recommendation on the Ethics of AI, adopted by 193 Member States, articulates principles of human rights, dignity, fairness, transparency, human oversight and environmental sustainability [2]. The RAM tool operationalises this Recommendation into an assessment of national readiness across legal, social, economic, educational and technological dimensions [3]. Several countries considered here (e.g. Palestine, Morocco, Egypt) have started or completed RAM-based assessments.

2.3 Data openness and ODIN

The Open Data Inventory (ODIN) evaluates national statistical systems on coverage and openness, with higher scores indicating more complete and accessible data [5–6]. For AI in the public sector, ODIN captures the maturity of the underlying data infrastructure: the extent to which key indicators are available, machine-readable, well-documented and licensed for reuse.

2.4 AI capabilities: OECD AI Capability Indicators

Rather than ranking countries, the OECD AI Capability Indicators characterise AI systems along multiple capability dimensions (language, social interaction, problem-solving, creativity, metacognition, perception, manipulation, navigation and multi-task integration) [4]. These indicators are highly relevant for the South Mediterranean because they highlight:

- The gap between high-resource languages and Arabic and other low-resource languages of the region;

- The need to evaluate imported models against local linguistic, social and institutional contexts.

2.5 Regional integration and digital trade

The UfM Regional Integration Progress Report shows that digitally delivered exports from North African economies have grown rapidly, but connectivity gaps, shallow digital trade provisions and limited cross-border research collaboration hinder deeper integration [7,11]. ESCWA’s work on digital trust and cybersecurity in the Arab region similarly emphasises that fragmented digital governance limits regional digital and AI ecosystems [8].

3. Data and Methodology

3.1 Data sources

The analysis is based on both primary and secondary data.

Primary sources:

- Official policy and government documents: national AI strategies, digital strategies, open-data policies.

- Laws and regulations: data protection, e-transactions, cybercrime.

- Government communiqués and reports from relevant ministries, regulators and councils.

Secondary sources:

- AI maturity tier framework proposed in the UN Secretary-General’s report A/79/966 [12]

- Government AI Readiness Index reports and technical notes [1].

- ODIN 2024–25 biennial report and country profiles [5–6].

- OECD AI Capability Indicators documentation [4].

- UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of AI and RAM methodological notes [2–3].

- ESCWA work on AI readiness, digital trust and cybersecurity in the Arab region [8].

- OECD and UfM reports on regional integration and digital trade [7,11].

- Academic literature on AI strategies in Arab and developing countries [9–10].

3.2 AI maturity tier framework

The methodology builds on the AI maturity tier framework proposed in the UN Secretary-General’s report A/79/966 [12], which defines:

- Tier 0 (T0) – AI nascent: very limited policy, infrastructure or skills; AI is largely absent from public-sector practice.

- Tier 1 (T1) – AI experimenters: early pilots and small projects; limited institutionalisation and scaling.

- Tier 2 (T2) – AI ready: basic enablers (data, infrastructure, skills, governance) in place to support AI deployment in priority sectors.

- Tier 3 (T3) – AI enabled: systematic integration of AI across public services and sectors.

- Tier 4 (T4) – AI developers: deployment at scale plus development of frontier models and exportable AI technologies.

For brevity, we use the T0–T4 notation throughout.

The initial tiering, based on an early desk review, classified:

- T1 – AI experimenters: Libya, Palestine, Syria

- T0 – AI nascent: Algeria, Tunisia, Lebanon

- T2 – AI ready: Morocco, Egypt, Jordan

This initial classification is retained as a baseline and refined through additional indicators.

3.3 Assessment domains

Country profiles are structured around five domains derived from the study’s analytical framework:

- Compute & infrastructure: Presence and scale of national data centres/HPC, access to GPUs/accelerators, energy reliability, backbone connectivity and international bandwidth.

- Data & governance: Availability of structured public datasets; data protection and sharing frameworks; openness and interoperability; ODIN scores as a proxy for statistical data infrastructure [5–6].

- Skills & institutions: AI workforce depth; academic programmes; national AI centres; regulator capacity; participation in UNESCO RAM and related capacity-building.

- Models & adoption: Reuse of pre-trained and foundation models; sector pilots (health, agriculture, mobility, public services); private-sector uptake; early generative-AI experiments.

- Strategy & cooperation (enablers): Status and implementation of AI/digital strategies; cross-government coordination; international partnerships (UNESCO, OECD, ESCWA, AU, Arab League, UfM); alignment with human-rights-based norms.

3.4 Quantitative indicators

Each country profile combines:

Government AI Readiness Score

ODIN 2024 overall score (0–100) [5–6]:

- Morocco: 77 (rank 24)

- Palestine: 75 (rank 33)

- Jordan: 72 (rank 44)

- Tunisia: 60 (rank 83)

- Egypt: 53 (rank 109)

- Lebanon: 33 (rank 180)

- Algeria, Libya, Syria: 28 (rank 187)

OECD AI Capability Indicators, used qualitatively to identify which capability dimensions (e.g. language and social interaction; perception and navigation; problem-solving and metacognition) are most relevant to national priorities [4].

4. Regional Overview and Comparative Findings

The initial comparative analysis highlighted:

- Wide disparities across the region, with most countries in T0–T2;

- Emerging national strategies with gaps in implementation and financing;

- Sector pilots in agriculture, health and mobility that rarely scale;

- Weak regional cooperation despite shared challenges.

The extended analysis confirms these points and adds three elements:

ODIN and AI readiness alignment: Countries with higher ODIN scores (Morocco, Jordan, Palestine, Tunisia) generally exhibit more advanced AI or digital governance and more active pilot ecosystems, but they are still limited by compute and skills.

Absence of T3–T4 countries: None of the assessed countries yet qualify as T3 (AI enabled) or T4 (AI developers). Even the more advanced rely predominantly on imported models and cloud infrastructures rather than domestic frontier-model development.

Regional integration constraints: UfM and ESCWA analyses show that despite growth in digitally delivered services, inconsistent connectivity, shallow digital trade provisions and limited data-sharing frameworks constrain regional scaling of AI-enabled solutions [7–8,11].

5. Country Profiles

5.1 Morocco

Tier: T2 – AI ready

Government AI Readiness Score: 41.78

ODIN 2024: 77/100 (rank 24)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- Digital Morocco 2030 (2024): national programme to modernise the economy and public services via digital technologies, with AI cited as a key lever.

- No dedicated AI policy yet, but national consultations launched in July 2025.

- First National AI Conference – “Assises nationales de l’IA” (1–2 July 2025, Rabat/UM6P): designed to shape a sovereign AI strategy; government communiqué and synthesis report published.

- Data Protection Law 09-08 (CNDP): baseline personal-data protection framework.

- UNESCO Category II AI centre in Rabat: public-sector AI workshops and pilots; active CNDP oversight.

Compute & infrastructure:

- Toubkal national supercomputer at UM6P (Top500-listed; ranked 98th at deployment).

- Plans for a 500 MW sovereign AI compute consortium (with NVIDIA), indicating significant ambition in AI compute.

- Responsible AI initiative (2025): partnership between the Ministry of Digital Transition & Administrative Reform and CNDP (Sept 2025) to build a national platform for responsible AI and an LLM framework tailored to Moroccan legal and linguistic contexts.

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Language and social interaction: Modern Standard Arabic, Moroccan Arabicfor digital public services.

- Problem-solving and metacognition: decision-support for taxation, planning and climate resilience.

- Perception and navigation: precision agriculture, water management, logistics and mobility.

Recommendations to move to the next tier

- Scale compute and data infrastructure and integrate AI into broader economic planning and budgeting.

- Establish a national AI strategy with clear plan and budget.

- Scale proven sectoral AI solutions across government services.

- Ensure AI hubs and the UNESCO centre drive public–private R&D and international collaboration.

- Provide funding for start-ups and scale-ups.

- Advance legal frameworks for rights-respecting AI (non-discrimination, privacy, security).

5.2 Algeria

Tier: T1 – AI experimenters

Government AI Readiness Score: 39.06

ODIN 2024: 28/100 (rank 187)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- National AI strategy efforts (2024) by a government-backed AI Council.

- National Strategy for Digital Transformation 2030 (2024).

- Personal Data Law n° 18-07 (adopted 2018; implementation strengthened in 2023).

- University-led pilots in agriculture, language processing and e-health.

- USD 11 million AI start-up fund (2025).

- First national HPC/AI centre announced in Oran (2025).

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Perception and navigation: oil, gas, logistics and environmental monitoring.

- Problem-solving: industrial optimisation and public-finance management.

To move to the next tier

- Adopt a dedicated AI strategy with a costed implementation plan.

- Expand compute capacity (data centres, HPC clusters, or regional hubs).

- Identify priority sectors and deliver high-impact use cases to build confidence and demand.

- Formalise AI centres as applied-research hubs linking universities, public institutions and private sector.

- Strengthen data governance and embed ethical and human-rights safeguards.

5.3 Tunisia

Tier: T1 – AI experimenters

Government AI Readiness Score: 43.68

ODIN 2024: 60/100 (rank 83)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- AI policy task force established.

- Data Protection Law 2004-63.

- University/government AI pilots in governance, health and education.

- Tunisia AI Roadmap (2021).

- Ongoing work to establish an AI strategy (target around November 2025).

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Language and social interaction: Modern Standard Arabic, Tunisian Arabic (Tounsi), and French digital services.

- Problem-solving and creativity: innovation in start-ups and e-government.

- Perception and manipulation: manufacturing and agriculture applications.

To move to the next tier

- Expand compute capacity (national DC/HPC clusters or regional hubs).

- Identify priority sectors and deliver high-impact use cases to build confidence and demand.

- Formalise AI centres as applied-research hubs linking universities and public institutions with private sector.

- Strengthen data governance and embed ethical and human-rights safeguards.

- Scale sectoral skills programmes.

5.4 Libya

Tier: T0 – AI nascent

Government AI Readiness Score: 33.25

ODIN 2024: 28/100 (rank 187)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- National AI Policy (2024) (Communications & Informatics Authority).

- e-Transactions Law 6/2022 (select provisions relevant to e-transactions and data).

- University of Tripoli operates a campus data centre installed with Almadar Aljadid & Huawei support (no public capacity figures).

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Language: basic Arabic and Libyan Arabic NLP for public information and e-government.

- Perception and navigation: simple applications in agriculture, logistics and climate monitoring.

- Problem-solving: simple decision-support tools in administration.

To move to the next tier

- Set up the national body to oversee execution of the AI Policy (as outlined in the policy).

- Establish a national AI strategy with a phased roadmap and multi-stakeholder coordinating body.

- Build minimum irreducible capacity across four domains:

- Computing (cloud/GPU access)

- Data (priority public datasets and governance)

- Skills (broad digital/AI literacy)

- Reuse of appropriate pre-trained models

- Stand up a national AI centre to manage shared resources, training, and engagement in international norms and standards.

- Launch basic pilots in priority public services (health, education, agriculture).

5.5 Egypt

Tier: T2 – AI ready

Government AI Readiness Score: 55.63

ODIN 2024: 53/100 (rank 109)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- Second National AI Strategy 2025–2030 (updated 2025), building on the 2019 strategy and the National Council for Artificial Intelligence.

- Egyptian Charter for Responsible AI (2023).

- Cloud-First Policy (2024) for government IT and e-government.

- Egypt chairs the African Union AI Working Group and the Arab League AI Working Group.

- Data Protection Law 151/2020, with executive regulations and the Personal Data Protection Center’s full operationalisation still pending.

- Compute capacity in the City of Knowledge and major universities, including Cairo University and Bibliotheca Alexandrina.

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Language and social interaction: Modern Standard Arabic, Egyptian Arabic (Masri), and English for public services and education.

- Problem-solving and metacognition: decision-support in fiscal policy, infrastructure planning and SDG monitoring.

- Perception and navigation: industrial automation and logistics.

To move to the next tier

- Issue PDPL executive regulations and operationalise the Personal Data Protection Center.

- Scale compute and data infrastructure and integrate AI into broader economic planning and budgeting.

- Regularly update the national AI strategy, including generative AI and high-risk use regulation.

- Scale sectoral AI solutions across government/services.

- Expand AI curricula and retain talent through competitive programmes and research facilities.

- Mobilise flexible funding mechanisms for start-ups and scale-ups.

- Ensure AI hubs drive public–private R&D and international collaboration.

5.6 Jordan

Tier: T2 – AI ready

Government AI Readiness Score: 61.57

ODIN 2024: 72/100 (rank 44)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- AI Strategy and Implementation Plan (2020).

- AI Ethics Charter (2022).

- Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL) No. 24/2023.

- Digital health transformation programme and sector pilots in agriculture and education.

- Digital Transformation Strategy (2021–2025).

- Open-data reforms with ODIN scores used as performance benchmarks.

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Language and social interaction: Modern Standard Arabic, Jordanian Arabic, and English services.

- Problem-solving and metacognition: analytics for social protection, climate resilience and public-finance management.

- Navigation and perception: transport, logistics and smart-city programmes.

To move to the next tier

- Scale compute and data infrastructure and invest in national data centres.

- Regularly update the national AI strategy.

- Scale proven sectoral AI solutions across government services.

- Ensure AI hubs drive public–private R&D and provide funding for start-ups/scale-ups.

5.7 Lebanon

Tier: T1 – AI experimenters

Government AI Readiness Score: 46.67

ODIN 2024: 33/100 (rank 180)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- No national AI policy or strategy at government level.

- Digital Transformation Strategy 2020–2030.

- Draft law to create a Ministry for AI and Technology (September 2025).

- Law 81/2018 (e-transactions & personal data).

- National Artificial Intelligence Strategy in Lebanese Industry (2020–2050).

- University/NGO hackathons and pilots; early AI policy discussions.

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Language and social interaction: Modern Standard Arabic, Lebanese Arabic, French, and English for public information and diaspora services.

- Problem-solving and creativity: media, cultural industries and innovation hubs.

To move to the next tier

- Publish and adopt a government AI strategy with priority sectors, KPIs, budget and clearly identified owners.

- Expand compute capacity via national or regional data centres/HPC clusters.

- Identify priority sectors and deliver high-impact use cases to build confidence and demand.

- Formalise AI centres as applied-research hubs connecting universities, public institutions and private sector.

- Strengthen data governance and human-rights safeguards.

- Scale sectoral skills programmes.

- Invest in public datasets and digitisation of government data to improve ODIN and AI readiness.

5.8 Palestine

Tier: T0 – AI nascent (with strong data/governance assets)

Government AI Readiness Score: 37.53

ODIN 2024: 75/100 (rank 33)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- Palestine’s AI National Strategy (Ministry of Telecommunications and Digital Economy, 2024; building on earlier strategy drafts).

- Use of UNESCO RAM to assess preparedness for ethical and responsible AI.

- Open Data Palestine portal (~40 datasets, 2024).

- Artificial Intelligence National Team established by the Council of Ministers.

- RISE-Palestine and SAFE-Palestine initiatives for technology-based start-ups (finance, mentorship, networking).

- Palestine Data Strategy 2022–2026, with emerging AI references and ESCWA support.

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Language and social interaction: Modern Standard Arabic and Palestinian Arabic for public services, govtech and citizen engagement tools.

- Problem-solving and navigation: humanitarian logistics, urban services and labour-market matching.

To move to the next tier

- Establish and operationalise a national AI strategy with phased roadmap and coordinating body.

- Build minimum irreducible capacity across computing, data governance, skills and reuse of pre-trained models, leveraging cloud-based and regional partnerships.

- Stand up a national AI centre to manage shared resources, training and international engagement.

- Launch basic pilots in priority public services (health, education, social protection).

- Strengthen partnerships between government, academia and private sector.

- Develop and refine laws and regulations for AI, addressing emerging ethical and societal issues; build on ODIN and UNESCO RAM strengths.

5.9 Syria

Tier: T0 – AI nascent

Government AI Readiness Score: 16.95

ODIN 2024: 28/100 (rank 187)

Key initiatives and relevant policies

- First national AI/digital events (2025).

- MoUs on telecom/digital solutions.

- Cybercrime and online regulations that touch digital content and security, but not yet tailored to AI.

Relevant OECD AI capability dimensions

- Language: basic text classification and translation in Modern Standard Arabic and Syrian Arabic for public information and humanitarian communication.

- Perception and navigation: low-risk applications in infrastructure monitoring and disaster response.

To move to the next tier

- Launch AI literacy programmes in partnership with universities, private sector and civil society.

- Establish a national AI/data centre (even at modest scale) to manage training, data curation and international engagement.

- Launch basic pilots in priority public services (health, education, agriculture) with clear safeguards.

6. Discussion

The extended analysis suggests five cross-cutting themes:

Data openness and AI readiness are related but distinct. Higher ODIN scores in Morocco, Jordan, Tunisia and Palestine sit alongside more advanced AI or digital strategies and active pilots, but do not guarantee higher AI maturity tiers. Data openness is necessary but not sufficient; compute, skills and governance remain binding constraints.

The region remains in T0–T2. None of the assessed countries yet meets criteria for T3 or T4. Even the most advanced rely on imported models and external cloud providers rather than domestic frontier-model development.

Regional integration is under-exploited. UfM analysis shows growth in digitally delivered exports but limited progress on digital trade provisions, connectivity, cross-border data-sharing and research collaboration [7,11]. Without progress here, AI-enabled services will remain fragmented.

AI system capabilities and local needs are misaligned. OECD AI Capability Indicators highlight that current models are strongest in high-resource languages and generic tasks [4]. For Arabic, local dialects (Darija, Masri, Levantine, etc.), Tamazight, Kabyle, and other low-resource languages, as well as context-sensitive public-sector use, significant adaptation, evaluation and governance are needed.

Ethical AI is normatively recognised but weakly institutionalised. Adoption of UNESCO’s Recommendation and RAM, as well as ethical AI charters, is growing [2–3]. However, concrete mechanisms, such as impact assessments, transparency requirements, oversight bodies and accessible redress, are still limited.

These dynamics create a two-speed AI trajectory: a small group of “AI ready but constrained” countries (Morocco, Egypt, Jordan, and to some extent Tunisia and Palestine) and a larger group of “AI nascent/experimenters” (Algeria, Lebanon, Libya, Syria). Without coordinated interventions, existing inequalities may deepen.

7. Policy Framework Recommendations

7.1 National-level recommendations

Adopt and implement costed AI strategies (T0–T1 countries): Algeria, Tunisia, Lebanon, Libya, Syria and Palestine should prioritise formally adopting and funding AI strategies with clear governance arrangements, milestones and KPIs.

Strengthen data ecosystems and ODIN performance: Use ODIN findings to identify gaps in coverage and openness; embed open-data reforms in data laws and digital strategies; explicitly link open data to AI research, evaluation and innovation [5–6].

Invest in compute and connectivity: Treat compute and connectivity as public goods: develop sovereign or shared HPC/GPU infrastructure and reliable electricity supply; expand fibre and 5G networks, especially in underserved areas.

Develop human capital and institutions: Expand AI-relevant curricula; support interdisciplinary programmes; create AI fellowships and return schemes; establish or strengthen national AI centres as hubs for training, R&D and international cooperation [8–10].

Operationalise ethical AI frameworks: Translate UNESCO’s Recommendation and OECD AI principles into context-specific regulation: algorithmic impact assessments, risk-based classification of AI systems, transparency and explainability requirements for high-risk uses, designated oversight bodies and accessible complaints mechanisms [2–4].

7.2 Regional and sub-regional cooperation

Shared AI guidelines and standards: Use Arab League, ESCWA and UfM platforms to develop common guidelines for AI in public services, cross-border data flows and generative-AI governance, reducing regulatory fragmentation [7–8,11].

Launch Mediterranean AI Fund

Regional compute and data-sharing infrastructure: Explore regional AI compute hubs and cross-border data spaces (e.g. for climate, health and mobility), with shared governance and equitable access.

Cross-border research and innovation programmes: Launch regional calls for projects on Arabic-language AI, local dialects (Darija, Egyptian Arabic, Levantine), Tamazight, Kabyle, and other low-resource language NLP, as well as socio-technical studies of AI impacts, leveraging academic and civil-society networks [9–10].

Digital trade and integration: Implement UfM recommendations on digital trade chapters in trade agreements, including data protection, interoperability and consumer protection, to amplify the benefits of AI-enabled services [7,11].

7.3 Monitoring and future research

- Establish mechanisms to update AI maturity tiers as new AI readiness, ODIN and regional integration data become available.

- Conduct detailed case studies of AI use in specific sectors (e.g. health, education, social protection, climate) and among civil society.

- Use OECD AI Capability Indicators in risk assessment, mapping where current capabilities (e.g. in language and social interaction) are insufficient for safe deployment in high-stakes domains.

8. Conclusion

Applying a UN-inspired AI maturity framework to South Mediterranean countries, enriched with AI readiness, ODIN and OECD AI Capability Indicators, reveals that the region is still at an early stage of public-sector AI capacity. Most countries remain AI nascent or experimenters; a smaller group is AI ready but constrained by limited compute, uneven data ecosystems and modest skills.

Nonetheless, improving open-data systems, emerging AI strategies, and growing engagement with ethical AI norms offer a foundation for progress. The central challenge is to move from fragmented pilots to coherent, rights-respecting and regionally integrated AI ecosystems. Achieving this will require both robust national reforms and stronger regional cooperation on standards, infrastructure and research so that AI supports inclusive, sustainable development rather than reinforcing existing inequalities.

References

- Oxford Insights. (2024). Government AI Readiness Index 2024. Oxford Insights. https://oxfordinsights.com/ai-readiness/ai-readiness-index/

- UNESCO. (2021). Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381137

- UNESCO. (2023). Readiness Assessment Methodology: A Tool of the Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics/ram

- OECD. (2025). Introducing the OECD AI Capability Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/06/introducing-the-oecd-ai-capability-indicators_7c0731f0.html

- Open Data Watch. (2024). Open Data Inventory (ODIN) 2024–25 Biennial Report. Open Data Watch. https://odin.opendatawatch.com/

- Open Data Watch. (2025). ODIN Country Profiles and Rankings 2024. Open Data Watch. https://odin.opendatawatch.com/Report/countryProfileUpdated

- OECD. (2025). Regional Integration in the Union for the Mediterranean 2025: Progress Report. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/09/regional-integration-in-the-union-for-the-mediterranean-2025_90fc8135.html

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA). (2024). Enhancing Digital Trust and Cybersecurity in the Arab Region. ESCWA. https://www.unescwa.org/sites/default/files/event/materials/13-%20Enhancing%20digital%20trust%20and%20cybersecurity%20in%20the%20Arab%20region%202400440E_0.pdf

- Demaidi, M. N. (2023). Artificial intelligence national strategy in a developing country. AI & Society. Advance online publication. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00146-023-01779-x

- El Gohary, E. M., & Elshabrawy, G. (2023). Assessment of the artificial intelligence strategies announced in the Arab countries. Al-Majalla Al-Masria lil-Tanmia wal-Takhtit, 30(4). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375860966

- Union for the Mediterranean (UfM). (2025). Annual Report 2024: Working Towards Economic Stability and Integration. UfM Secretariat. https://ufmsecretariat.org/annual-report-2024/

- United Nations. (2025). Innovative voluntary financing options for artificial intelligence capacity-building: Report of the Secretary-General (A/79/966). United Nations General Assembly. https://www.un.org/digital-emerging-technologies/sites/www.un.org.digital-emerging-technologies/files/A_79_966-EN.pdf